How the Allies Cracked the German Enigma Machine

Bletchley Park, Alan Turing, and Predecessors to the Modern Computer

In my post on the Vigenère Cipher I ended by saying:

The most interesting story in the history of cryptology is probably the story of the German Enigma machine, Bletchley Park, Alan Turing, and the Bombe. It is the story that sparked my entire interest in history and cryptology in fact. But that’s another story, for another day, and another post.

Today is that day, and this is that post.

The first time I ever thought of history as something other than a series of facts to be memorized for a school quiz or test was when I learned about the Allied codebreaking effort in WW2.

It occurred to me that the history we learn is only set in stone now; at the time it was happening, things were profoundly uncertain, and the choices and effort of individuals would have huge ramifications on what would happen.

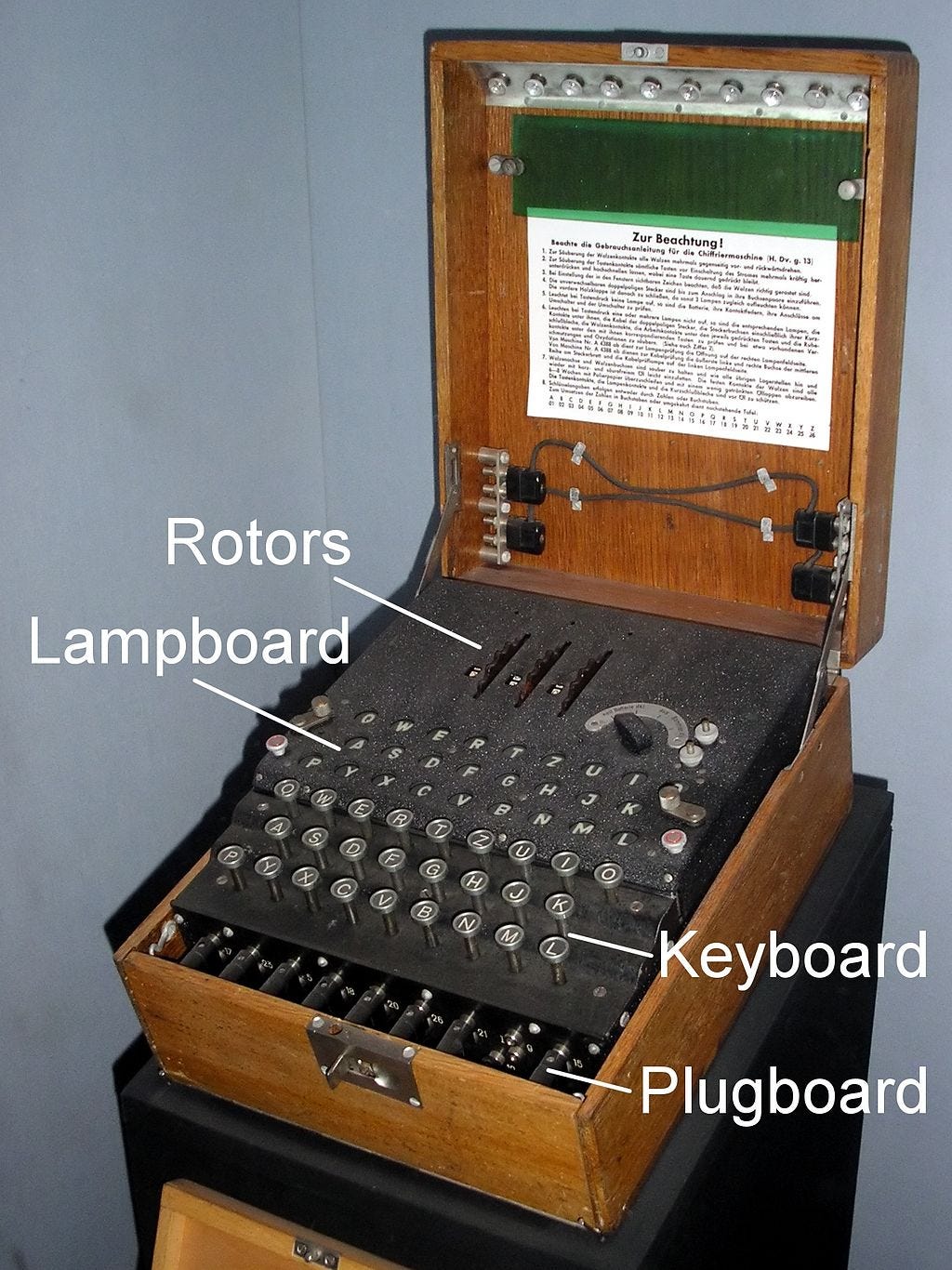

In WW2 the Germans used a machine called the Enigma Machine to encrypt their military communications. It looked like this:

It worked like this:

At the beginning of each day the operators would have settings for the machine that they would all use. The settings were which letters in the plug board to connect, and which starting position to have the 3 non-static wheels on. The operator who wished to send an encrypted message would type a letter and an electrical current would run through the plugboard, swapping the pressed letter for another letter, then through all the wheels swapping the input letter every step of the way for the new “input” of the next step, before finally lighting up the output letter on the lampboard. The wheels would rotate as the message went along, further complicating any effort to crack the cipher.

The difference between knowing what your enemy in the largest war of all time are saying amongst themselves in secret, and not knowing, is enormous. British Intelligence knew this and started a massive crowdsourced initiative to find a way to crack it. They didn’t know how they would do it so they casted a wide net. Are you excellent at crossword puzzles? Come to Bletchley Park (where the Enigma breaking efforts were centered) and help the war effort. Are you a brilliant mathematician? Come help. Are you a linguist? Get over here.

Note: I will refer to the allied codebreakers at Bletchley Park as ”they” because it was a collective effort, but know that by far the most important of the individuals working on the problem there was a man named Alan Turing. Teasing out just how much of the success should be attributed to him vs. the rest of the people working at Bletchley Park is beyond the scope of this post. While we are doing caveats about who deserves credit, it’s also a very under discussed part of this story that Polish intelligence, using information from French intelligence, had a huge head start on this, with Marian Rejewski being the Polish equivalent to Alan Turing. Polish intelligence shared this information with French and British intelligence, greatly helping them with their efforts.

Ultimately, if the Germans were sufficiently successful at not letting anything fall into the Allies hands (e.g. an actual enigma machine, the daily settings to be used, any unencrypted messages) there was nothing the Allies could do. The allies did manage however to get their hands on some working Engima machines, and crucially found that the Germans would always start their messages by describing the current weather. They realized with an intimate knowledge of the inner workings of Enigma machines and a very strong guess for what the beginnings of a message actually said, they could use brute force to reverse engineer that day’s settings for the Enigma machine, thus allowing them to have intimate knowledge, for the rest of the day, as to what the Germans were thinking, saying, planning, and doing. Unfortunately for the Allies, brute forcing all the possibilities was significantly easier said than done. They didn’t have modern computers which can do ludicrous numbers of calculations per second. They created a machine called the Bombe. It looked like this.

It was a bit like having a bunch of enigma machines in one, continually trying different settings for the Enigma machine, and seeing if the encrypted messages of the day outputted nonsense or actual messages. It was more complicated and a bit less automated than that; it involved the people saving the Bombe some time by making sure it wouldn’t have to check settings that they were sure weren’t being used, and in return the Bombe would massively narrow down the possibilities for the people to do the final leg of the cryptanalysis and figure out the exact settings of the day.

For higher level communication the Germans used something even more sophisticated than the Enigma machine, called the Lorenz SZ 40/42, which led to the allies creating the Colossus. The bombe and the Colossus were big steps forward on the path from sticks and stones to modern computers, as were the post-war efforts of Alan Turing.

Exactly how impactful the successful work of the people at Bletchley Park was to the allied war effort is a subject of spirited debate amongst historians. Undoubtedly it was beneficial to the allies and made their victory quicker and less costly.

Alan Turing was a homosexual, which was illegal in the United Kingdom during his life. During a police investigation of a burglary of his own home, he admitted to the police that he was a homosexual. As a result he was convicted of indecency and given the choice between imprisonment or probation with injections of a synthetic hormone. He chose the probation and hormone “therapy.” It made his body undergo undesired and unpleasant changes. He was stripped of his security clearances and no longer able to help British Intelligence. He died in 1954. It’s hard to think of a person in all of British history whose net effect on society was more positive than Alan’s, and his treatment by his own government for having a sexual relationship with consenting adults who happened to be male, instead of female, is despicable. Starting in 2009 the British government, via various official statements, petitions, bills, etc. began to apologize for their bigoted law that vilified and criminalized a man whose unique intelligence and efforts were instrumental in saving untold numbers of lives in the largest war in all of human history.