The year is 63 B.C.

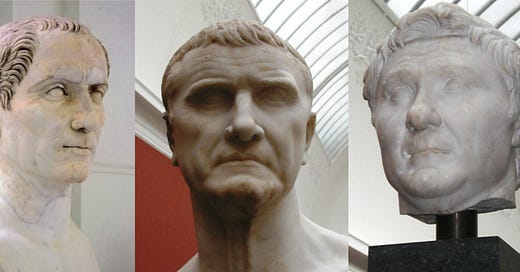

Pompey Magnus is the greatest military leader in all of Rome. Marcus Crassus’s wealth is indescribable. They hate each other.

Julius Caesar wields significantly less power than either. He is hungry for more.

The Roman Republic is 570 years old. It won’t last another 20.

Let me pause the story here just to give a very quick and rough overview of the political structure of the Roman Republic:

Each year two ‘consuls’ are elected as the head of state. Imagine two Presidents or Prime Ministers serving together.

Rome also has a ‘senate’ that acts like representative legislative bodies act in many modern day democracies.

Rome had a political position called ‘Tribune of the Plebs’. Their job was to look after the Plebeians (commoners), and they had a ton of power with which to do that. However, whenever they took their job very seriously in a way that was a threat to the existing power structure the aristocracy would simply assassinate them. Problem solved.

Roman society operated on a Patron-Client relationship. Think of The Godfather; "Someday, and that day may never come, I will call upon you to do a service for me."

Ever since exiling their last king in 509 BC the Romans had an intense desire to prevent any one individual from becoming too powerful, yet simultaneously would try to instill in it’s citizens an intense burning ambition.

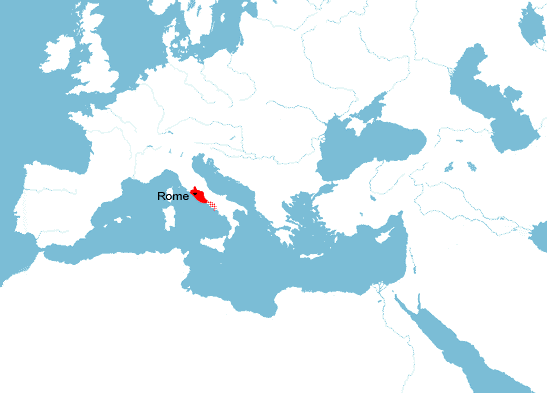

The intense ambition that Roman society instilled in it’s population, combined with it’s sophisticated political structure served it well. It grew from this:

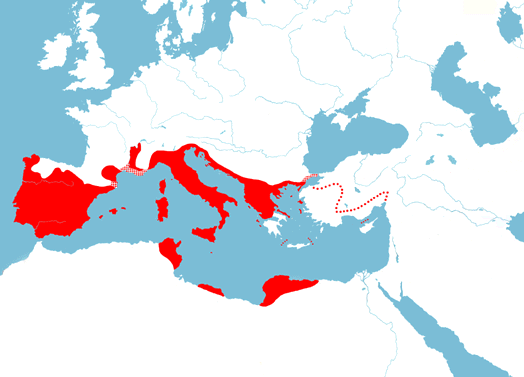

To this:

Caesar and Pompey will expand these borders even further (Caesar in what we call France, Belgium, and Britain; Pompey in what we call Turkey).

Rome’s political system was designed to govern a small agrarian city-state. It was now being asked to govern a society that sprawled all around the Mediterranean, was rich beyond it’s founders wildest dreams, and had a military that was almost perpetually at war. These wars took many small landowners off to faraway lands, and brought back many slaves from enemies defeated abroad. Wealth inequality skyrocketed as the wealthy bought up the conquered lands and those of the smaller farmers who went off and did the conquering; utilizing the enormous influx of slavery to work the land exacerbated this. This was, via the corrupting power of wealth, destabilizing to the political system.

A few consecutive Tribunes of the Plebs used their position to try and fix the problems of the increasing wealth inequality, mainly by trying to have an existing law that limited personal landholdings to 500 jugera (roughly 311 acres), actually enforced. They were promptly assassinated by those who had no interest in seeing their estates broken up and distributed to others. This blatant ignoring of existing laws and political assassination of those who tried to enforce them delegitimized the political system, and meant that those who wanted to make change or at least enforce existing law also had to go around the political system and also had to resort to violence, which further delegitimized the political system. Soldiers allegiances were shifting from the state, which was becoming a less legitimate source of authority, to the individual generals who led them.

From 83-81 BC there was a brutal civil war between the followers of the generals Sulla and Gaius Marius. Rome was finding that once you injected violence into the political system, it was very difficult to get it out.

Back to our story….

Pompey is returning from the East after successfully defeating Mithridates, the King of Pontus, in the Third Mithridatic War. You can tell how much of a thorn in Rome’s side this guy was by the fact that this was their third war with him. This victory was total and it added a huge amount of territory and wealth to Rome. Pompey’s wealth soared; and he now had an army of intensely loyal veteran soldiers following him. Remember that Client-Patron relationship I told you about earlier? Well a lot of these Kings in the territory that Pompey just conquered had their lives spared by Pompey in exchange for becoming his client, which made all of their citizens his de facto clients. To the Romans who were ever fearful of one man seizing ultimate power, Pompey was now terrifying.

Pompey wanted the Senate to pass a bill to rubber stamp some deals he made with the rulers of these recently conquered territories, and he wanted land grants for his veterans. The influential members of the Senate were vehemently opposed to this, they didn’t like that Pompey had made these deals in the East without Senate approval and they especially didn’t want him to be any more powerful than he already was. Pompey was finding that he was a much more adept general than politician.

Crassus and a bunch of his wealthy clients screwed up in a tax situation in the East. Basically when Rome wanted to extract taxes from a territory they would accept “bids” on the “contract,” the bidders promising some amount in tax revenue from the territory. Rome would then pick a bidder (generally whoever was promising the most tax revenue) to be in charge of collecting taxes in that territory. Anything the winning bidder could squeeze out of the territory beyond the winning “bid” they were free to keep for themselves. In an effort to win the tax contract for some territory in the East, Crassus and his friend’s had promised a great deal more money than they were able to extract, and were thus underwater on the deal. They were looking for a bailout, and some principled members of the Senate, lead by Cato the Younger, were vehemently opposed to it.

Three years later Caesar was coming back from a successful governorship in modern day Spain. This successful governorship involved a lot of warfare, an activity at which Caesar was exceptional. He intended to run for Consul. For his military successes in Spain Caesar was going to be awarded a triumph. A triumph was the biggest honor a military leader in Rome could get. They were rare. It was a giant parade in a general’s honor, with lots of pomp and circumstance. There was a problem though, because of some uninteresting technicalities of the Roman system, Caesar could not both celebrate his triumph upon his return to the city AND run for Consul. Well, he could, but the Senate would have to bend the rules for him (and the rules had become very pliable over the last couple generations in Rome), which they did not want to do. Caesar did a remarkable thing which showed just how brightly his ambition burnt, and forfeited his triumph so he could run for Consul. He sacrificed the ultimate glory for the chance to gain more political power.

So let’s recap. Pompey is popular and powerful almost beyond measure, but is being stonewalled in the Senate from fulfilling promises to his veterans, whom he owes his popularity and power to. Crassus is tremendously wealthy and has much of Rome in his pocket, but is being stonewalled by Cato the Younger and his allies in the Senate on the bailout he and his business associates want.

Caesar sees the two most powerful men in Rome not getting what they want due to the obstruction of different factions of the Senate, and sees an opportunity. Caesar approached Crassus, whom he already had a relationship with as Crassus had been bankrolling Caesar’s political career. Caesar approached Pompey. He made a proposition to them. What if we forge a secret alliance and support each other’s ambitions? With our power and influence combined, none in the Senate (or out of it) can stop us from getting what we want. Crassus and his friends can get their bailout. Pompey can get his actions in the East rubber stamped plus land grants for his veterans. Caesar can get his first Consulship. Crassus and Pompey were convinced. This informal alliance became known as the First Triumvirate. The alliance was further formalized and strengthened by Pompey marrying Caesar’s daughter.

Caesar, in bringing together the two most powerful men in Rome and solving their problems for them, made himself the master of both. And this was Caesar’s masterstroke. The arrangement, for a time, worked out great for the three of them, much to the detriment of everyone else in Rome who tried to wield influence. Caesar won his consulship and his co-Consul was a man named Marcus Calpurnius Bibulus. Bibulus was so thoroughly sidelined that the Consulship was jokingly referred to as "The Consulship of Julius and Caesar.” Cato was incensed and disgusted by the state of affairs.

Eventually Crassus, the most senior of the Triumvirs, decided to make war with the Parthian Empire (roughly modern day Iran). Crassus had grown jealous of the fabulous military accomplishments of his fellow Triumvirs and thought going to war with the rich Parthians would be a great way for him to catch up to Pompey and Caesar in the egotistical competition for military glory, not to mention the riches to be gained from a successful campaign. Unfortunately for Crassus, the Parthians were no slouches, and he did not have the military acumen of Pompey or Caesar. At the Battle of Carrhae, the Romans, led by Crassus, were handed one of the most crushing defeats in their long history. It’s a pretty fascinating battle pitting two very different types of armies against each other, but the military specifics of it are another story for another post. After Crassus’ death the Parthians were said to have poured molten gold down his throat in a symbolic gesture, mocking his insatiable thirst for wealth. His severed head was used as a prop in a play performed for the Parthian King, which he relished.

Around this same time, tragically, Julia, daughter of Caesar and wife of Pompey, passed away during childbirth. After Julia’s death Caesar and Pompey’s relationship soured, and with Crassus gone the Triumvirate was no more. There was no one left in Rome to check Caesar or Pompey’s power, except the other. Lines were drawn. Sides were chosen. Most threw in their lot with Pompey. After Caesar crossed the Rubicon, a civil war ensued that lasted for four years. Pompey waged the war from the position of “If you’re not with us, you’re against us.” Caesar went with the approach of “If you’re not explicitly with Pompey, you’re with us.” Caesar routinely offered clemency to those he defeated, whereas Pompey’s camp was taking no prisoners. As word of this spread, those fighting for Caesar had to fear for their lives if a battle was lost, and thus fought more ferociously, whereas Pompey’s troops could feel safe surrendering and defecting. The tide of the war was ebbing in Caesar’s favor. Pompey’s age (he was six years older than Caesar) was also seeming to become a factor, as he prosecuted the war with much less speed and certainty than Caesar. At one point Pompey and his troops fled to Egypt. The leaders there seeing which way the wind was blowing assassinated him. Caesar arrived a few days later and we are told he was appalled, and cried when he was given Pompey’s seal ring. Pompey’s supporters continued the war effort for a little while thereafter, but the end result was a Caesarian victory. Caesar was proclaimed dictator for life and the last embers of democracy in the Roman Republic faded.

Caesar’s dictatorship was rather productive, as he was very hardworking and intelligent, and was able to circumvent the horrific political gridlock that had calcified in Rome over the last century. He planned an invasion of Parthia to avenge the defeat of the Roman legions under Crassus. He never would get to follow through on those plans. The men whose power now wrested in his hands bristled at their now purely ceremonial positions. He was warned by a seer that harm would come to him no later than the Ides (15th) of March. On the date he is said to have commented to the seer on his way to the theatre “The Ides of March has come and I’m still here,” the seer responded “Aye Caesar, the Ides of March has come, but it has not yet gone.” When he entered the theatre the signal was given and the senators surrounded him and pulled out their knives. He was stabbed twenty-three times, including by Brutus, whose mother was the love of Caesar’s life. Caesar’s dying words are a matter of dispute, some sources tell us he said “You too my son?” as he saw Brutus taking part in the assassination, while Suetonius tells us he merely covered his face with his toga and silently accepted his fate. Shakespeare of course penned the line as “Et tu, Brute?”

His assassins had no real plan for how to transition back into a democracy, nor did they realize how much popular support Caesar had. A rather chaotic situation with a power vacuum ensued. Nature abhors a vacuum.

Another Triumvirate was created, which also fell apart, and also resulted in a civil war. This civil war was won by a man we now know as Augustus, the great nephew of Caesar, whom Caesar, in his will, adopted as his son and named as his heir. He was the first emperor of the Roman Empire and ruled for 41 years.