Imagine a lake that is surrounded by five villages. All the villages use the lake for their drinking water, and all the villages release their wastewater back into the lake. Every village has two choices:

Treat your wastewater before releasing it back into the lake.

Don’t treat your wastewater before releasing it back into the lake.

It costs an individual village $50,000 to treat it’s wastewater.

It costs an individual village $20,000 times the total number of villages that do not treat their wastewater, to treat their drinking water.

Should a village treat their wastewater before releasing it back into the lake?

Let’s look at this more closely.

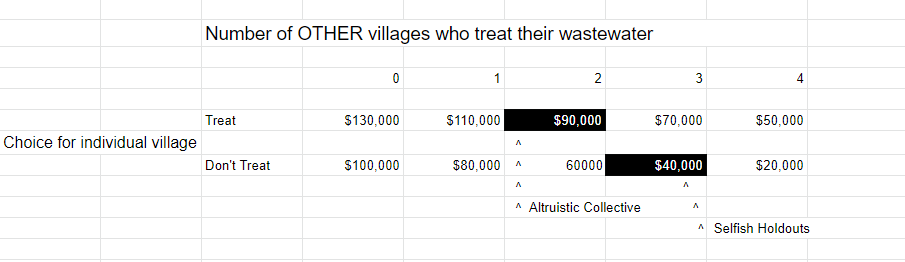

Look at the ‘Treat’ row as compared to the ‘Don’t Treat’ row.

No matter how many other villages decide to treat their wastewater first, an individual village’s best option is to not treat their wastewater. This also holds true for the other villages; the logical conclusion is that every village doesn’t treat their wastewater, and ends up paying $100,000 annually to treat their drinking water. If they all had just treated their own wastewater to begin with, they would be paying only half that, $50,000 a year. We have a pretty vexing result here that seems paradoxical.

Five entities all acting in their own rational self interest are ending with worse individual outcomes than if they had acted altruistically. And yet, no individual village ought to do anything differently.

If one village sees the wisdom in treating it’s wastewater we have the below situation:

The village is costing itself an extra $30,000 a year and saving all the other villages $20,000 a year. Not a good result for the village trying to act altruistically. Maybe there are other options…..

A closer look will show that three villages can save themselves $10,000 each by forming a collective and all agreeing to treat their wastewater, but getting such an arrangement in place would be very difficult. Why? Look at what happens to the other two villages cost:

They each save themselves $60,000 by continuing to not treat their wastewater while the three villages acting selflessly are each only saving themselves $10,000. Each village wants very badly for the other villages to to treat their wastewater but is disincentivized to do so themselves.

This problem was introduced by Lloyd Shapley and Martin Shubik in 1969. It is a specific example of what has become known as “The Tragedy of the Commons” from an article written by Garrett Hardin in 1968. The concept was originated in 1833 by an economist who described the hypothetical effects of many people grazing their animals on common land. In the original example nobody is incentivized not to let their own animals graze on the collective land, but in so doing they end up overexploiting the resource to everyone’s detriment.

In Game Theory these are called “n-person prisoner’s dilemmas.”

“Hardin suggests that the remedy in this kind of situation is for all the villages jointly to agree to force all the villages to join in a common coalition. After all, such an application of common force would benefit every village. He argues that ‘mutual coercion mutually agreed upon’ must be the central principle of a new morality, if we are to deal with n-person prisoner’s dilemmas which threaten the future of our planet.”

Game Theory and Strategy (Philip D. Straffin)

The amount of real world situations that can be thought of as examples of these are numerous.

In my mind the largest and trickiest is Global Warming.

Take the difficulty involved in the lake polluting example and now add in the fact that the beneficiaries and sufferers of collective action or inaction are not even born yet; whereas those who are being asked to sow will be long gone before the rewards are reaped. If we can’t rationally agree to act in the common good of ourselves and our neighbors, can we really be counted on to do so in the common good of people who won’t even be born for 100 years?

Humanity can do it but it will take a tremendous collective effort; it will require a lot of politicians and their constituents to act against their own basest urges. It will require scientific funding and experimentation. It will require consumers to be regularly inconvenienced for less than a drop in the bucket of the problem. It will require corporations and their shareholders to consider other factors relevant to their decisions besides money. It will require all of these to be done even when it would be easier to just point at the other’s who aren’t doing their part and use that as an excuse to also not do one’s own part. It will require motivation (some carrots and some sticks) to get those who aren’t chipping in, to chip in .

It should be noted that many times over humans have been able to (and continue to) circumvent the mathematical conclusions of games like this that are, essentially, “rigged” against collective altruistic action. Elinor Ostrom won the 2009 Nobel Prize in Economics for demonstrating many examples, you can read all about them in her book Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective.

As of March 2017 leaded gasoline is only being used for automobiles in Algeria, Yemen, and Iraq. Those three countries account for just 1.37% of the world population. The benefits of leaded gasoline not being used anymore are huge.

The hole in the ozone layer we used to always hear about is recovering nicely. In 2019 NASA reported that the hole was the smallest it had been since it’s discovery in 1982. This was done by global society agreeing to stop producing ozone-depleting substances (ODS).

Nice post.

"He argues that ‘mutual coercion mutually agreed upon’ must be the central principle of a new morality, if we are to deal with n-person prisoner’s dilemmas which threaten the future of our planet.”

I found this nugget particularly enlightening.